Chapter 1: Introduction;

Chapter 2: Persistence

- In functional languages, you get “persistence” for free

What is persistence? In imperative languages, data structures rely on destructive assignment, i.e overwriting variables, which means that once yoiu perform some operation on a data structure, you end up changing its internal state and you lose the “old” version of the data structure forever. These data structures are known as ephemeral structures. In functional languages, since data is immutable (for the most part), new structures are “wrappers” around old structures, and so you always have a handle to the old versions. For instance, lists can be destructured to a head and the rest, giving you the old version. I might be misunderstanding this?

- Persistance breaks amortized analyses

- Strict languages are clearly superior to lazy languages in at least one regard: analyzing runtimes, since in lazy languages, it is very, very hard to determine if a piece will ever be run

You can think of ephemeral structures as those being used in a single-threaded fashion, while persistent structures are shared across multiple threads (in a read-only fashion).

… from the point of view of designing and implementing efficient data structures, functional programming’s stricture against destructive updates (i.e., assignments) is a staggering handicap, tantamount to confiscating a master chef’s knives. Like knives, destructive updates can be dangerous when misused, but tremendously effective when used properly. Imperative data structures often rely on assignments in crucial ways, and so different solutions must be found for functional programs.

This book is about the fact that, even though immutability and other functional features may seem limiting, it is possible for purely functional data structures to be as efficient (asymptotically) as their mutable counterparts. Furthermore:

Until this research, it was widely believed that amortization

was incompatible with persistence [DST94, Ram92]. However, we show that memoization, in the form of lazy evaluation, is the key to reconciling the two.

Chapter 3: Some Familiar Data Structures in a Functional Setting

TODO

Chapter 4: Lazy Evalutation and $-notation

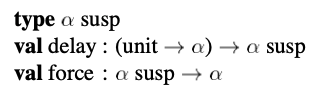

Supporting lazy evaluation in a strict language involves the addition of two primitives: - Delay - Force

- Wrapping calls with delay/force is very verbose, so this chapter introduces a more succint, neater $-based syntax

- Prepending an expression with $ will suspend it - $ parses as far to the right as possible – you can nest suspensions –

$$e - The $-notation is integration with pattern matching as well - avoiding the need for nested case expressions

Example (ML-esque pseudocode):

integer, T stream => T stream

fun take(n, s) =

delay(fn () => case n of

0 => Nil

_ => case (force s) of

Nil => Nil

| Cons(x, s') => Cons(x, take(n - 1, s')))Now, using the neater $ integration with pattern matching (matching against a pattern prepended with $ will first force the expression and then match against the stuff after the $):

integer, T stream -> T stream

fun take(n, s) = $case (n, s) of -- note the $ before case, the result type is a stream so this is necessary

(0, _) => Nil

(_, $Nil) => Nil

(_, $Cons(x, s')) => Cons(x, take(n-1, s'))Why isn’t this equivalent to the methods above?

integer, T stream -> T stream

fun take(n, s) = $Nil

| take(_, $Nil) = $Nil

| take(_, $Cons(x, s')) = $Cons(x, take(n - 1, s'))Because in this method, the input stream is forced at the time when take is applied – not when the stream returned by take is forced! This is unecessary computation and goes against the lazy semantics one would expect take to have.

The difference a lazy list and a stream is that a lazy list, once forced, performs the entire computation – it is monolithic. Streams, on the other hand, incrementally generate the next result.

An example of this behaviour can be expressed by the append function on lazy list and streams:

For lazy lists:

fun s ++ t = $(force s @ force t)^ when this is force, the entire computation is performed.

And for streams:

t stream, t stream -> t stream

fun s ++ t = $case s of

$Nil => force t

| $Cons(x, s') => Cons(x, s' ++ t)^ when this is forced, only the first step in the computation of appending the streams is performed.

Chapter 5: Fundamentals of Amortization

Implementations with good amortized bounds are often simpler and faster than implementations with equivalent worst-case bounds

What is amortization? Amortization is when you apply bounds on entire sequence of operations rather than a single operation. For example, you may want a sequence of n operations to be bounded by O(n), but this doesn’t necessarily imply that every single operation must take O(1). This allows for more flexibility in implementation.

When proving amortization bounds, you prove that at any stage in the computation of this sequence, the accumulated amortized costs are less than the actual accumulated costs – the difference is called the accumulated savings.

Banker’s Method

Each operation has a cost, allocates “credits”, and spends credits.

\[ a_i = t_i + c_i + \bar{c_i}\] Each credit must be allocated before it is spent, i.e \(\sum{c_i} \geq \sum{\bar{c_i}}\) Proofs using this method need to show that the invariant above is maintained at every stage of the computation.

Credits are associated to individual locations in the data structure

No credit must be spent more than once

Physicist’s Method

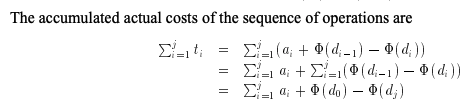

- Define a potential function \(\Phi\) that assigns, to each state (i.e the state of objects in the internal representation of the data structure, after an operation is applied) a “potential” that represents a lower bound on the accumulated savings. There, the amortized cost after some step is defined to be: \[ a_i = t_i + \Phi(d_i) - \Phi(d_{i-1})\] where \(d_i\) and \(d_{i-1}\) are outputs of step i, i-1 repsectively.

- Typically, the potential function \(\Phi\) so that it is intially zero and always non-negative

because the potential form a “telescoping series” (i.e same value alternating signs)

Example: Queues

- Queue are often implemented as a pair of lists, F and R

- The three main operations on a queue are:

- head: get the first element

- tail: drop the first element

- snoc: append an element to the rear of the queue (snoc == cons to the right)

fun head(Queue {F = x::f, R = r}) = x

fun tail(Queue {F = [x], R = r}) = Queue {F = rev r, R = []}

| tail(Queue {F = x::f, R = r}) = Queue {F = f, R = r}

fun snoc(Queue {F = [],...}, x) = Queue {F = [x], R = []}

| snoc(Queue {F = f, R = r}, x) = Queue {F = f, R = x::r}^ not including error handling

The invariant in this implementation is that F can only ever be empty if R is also empty. This means that, when tailing the queue, if F is a single element list, it gets replaced by the reverse of R (since R stores the rear of the queue _in reverse order, in order to support O(1) append)

Using the banker’s method We define the credit invariant that the list R always has a number of credits equivalent to its length. snoc calls on non-empty queues have an amortized cost of two now, since they allocate one credit to the R list. All other operations take 1 step, except the tail calls that reverse the R list – which take m+1 steps, and spend the m credits, resulting in an amortized cost of 1!

Using the physicist’s method Same idea, the potential function is the length of the rear list.

Note that, even though the proofs are nearly identical here, the physicist’s method is almost always simpler since all we need to do is define the potential function and then calculate. In the banker’s method, on the other hand, we need to define how many credits does each operation allocate and what the credit invariant is. Note that there are infinitely many valid credit assignments that maintain a given credit invariant, which just adds to the confusion.

Why does this analysis break if we have persistent data structures?

Consider a persistent queue q, and you call tail n times on this queue. The reason why amortized analysis breaks is that you can only ever spend the accumulated savings once! In the banker’s method, there is an invariant that credits once allocated, can only be spent once. In the physicist’s method, there is an invariant that output of a step must be the input for the next step (in order to get a telescoping series). Intuitively too, this makes sense.

Chapter 6: Amortization and Persistence via Lazy Evaluation

TODO